Back in England, I used to get really annoyed when people spelled my name wrong. You would think that there aren’t many ways to misspell “Melissa Maples.” You’d be wrong. Countless pieces of mail arrived at my door addressed to “Mellisa Staples,” “Malisa Tables,” or even “Melinda Gables.” I used to phone the relevant companies and ask them to correct the spelling. Sometimes it helped; mostly it didn’t.

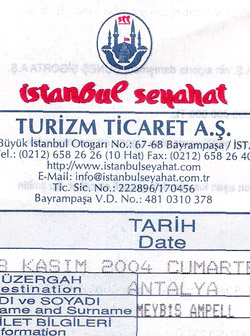

Since I’ve moved to Turkey I’ve had to loosen my expectations of what people will and will not be able to spell. I’m lucky in that “Melisa” (usually spelled with one s) is quite a common Turkish name; “Maples” on the other hand is not, go figure. A word spelled that way in Turkish would be pronounced like one who doesn’t have a road map— Map-less. When I say “May-pulls,” they don’t know what to do with it. Sometimes they spell it “Meypuls” or “Meypılz” (the i without a dot being a letter we don’t even have in English, but which has a very similar sound to the schwa in Maples), but mostly they just get completely confused and write down some seemingly random string of letters. The image I’ve posted here is a scan of a bus ticket I purchased three years ago, where even after I repeated my name three times, the girl at the ticket counter couldn’t understand how to type it in, and asked to see my passport so she could copy the name down directly. However, I guess by that point she was so flustered by our miscommunication that even with my passport in front of her for reference she still recorded my name as “Meybis Ampell.” I giggled and pointed out that she’d still gotten it wrong, to which she shrugged like, “what do you want from me, I can’t help it if foreigners have confusing names…”

I’ve since come to the realisation, that what with the differences in alphabet and pronunciation systems between Turkish and English (some of which are quite significant), it’s unrealistic to demand that people here use the English alphabet to spell my name in their language. They do use a different alphabet here, after all, even though it too is based on the Latin character set. So nowadays I’m just happy if they pronounce my name correctly, and as far as I’m concerned they can use whatever Turkish letters they want to represent the sounds of my name when they write it down. After all, if a Chinese woman moved to an English-speaking country, we wouldn’t be expected to use Chinese characters to write her name down— we’d just use our own writing system and do the best we could to approximate the correct sounds with our alphabet.

I saw a story on NTVMSNBC recently about an English woman named Wendy Phyllis who attained Turkish dual citizenship in 1999 and is now going to court because she says the Turkish government changed her name for her Turkish identity papers without her permission, and it’s causing problems when she travels to England because the UK authorities claim the name on her Turkish passport does not match her given name. The issue is that in the Turkish alphabet, the name Wendy Phyllis would be spelled “Vendi Filiz,” and that’s how they’ve recorded her name on her identity card and passport. As the article states, there isn’t even a W in the Turkish alphabet, and the letter combination Ph in Turkish has no relation to an F sound, so that needed to be changed as well.

My issue is with the UK government (and presumably Ms. Phyllis) claiming that the Turkish government has actually changed Ms. Phyllis’s name. They haven’t changed it, they’ve just converted the spelling to their own alphabet so that they can read the name correctly and with ease. As far as I’m aware, this is common practice in the UK and most other countries, when a foreign national immigrates and his given name was originally written in an alphabet or syllabary that the people in his adopted nation can not be expected to be familiar with. So what, are we not allowed to transliterate names anymore when people immigrate? If Wendy Phyllis cannot be written as Vendi Filiz in Turkey to allow Turks to be able to read it, then I guess when we welcome 梁國平 or تركي الحمد to an English-speaking country we’re not allowed to change the writing of their names, either, because it might cause them problems when they’re traveling to their respective home countries. If that’s the game we’re going to start playing, then fair is fair. Obviously when we talk about different writing systems and/or alphabets there’s a matter of degree, but who decides where that line is drawn? The UK government? Please, I don’t think so. If it’s reasonable to transliterate names for ease of reading, then I think it’s reasonable to transliterate across the board. Making names possible to read is not a privilege of English-speaking nations only.

I certainly won’t complain if and when my Turkish identity papers say “Melisa Meypılz” on them. That is, after all, the best approximation of my name using the Turkish alphabet. Likewise I wouldn’t blink when traveling to Korea and having my name transliterated into hangul, or katakana in Japan. Part of going to a foreign country is accepting these language differences. I, for one, embrace them.